Gender Justice and Circular Economy

Gender Justice means recognising the care (e.g., care of children and senior citizens) and reproduction provided in households, communities and nature to sustain the social and environmental context of human life. This work is largely unpaid and remains unvalued, but is also crucial to counter the negative effects of the market economy upon both humans and the environment, granting the regeneration, restoration and healthy functioning of people and environments.

Read the full report:

Check out our infographic:

Key Findings of Gender Justice in Circular Economy

Definitions and explanations about key terms relevant to gender justice.

How does gender justice relate to the transition to a circular economy?

Explore relevant examples.

Where to learn more.

Key concepts

Gender

Gender is not synonymous with women.

It indicates socio-cultural norms that shape and sanction “feminine” and “masculine” behaviours, which are complex and change across time and place [European Commission 2020]. A feminist political economy perspective frames gender as a function of the social division of labour, rather than as a predetermined category, and investigates its relation to how economy is organised, performed, and valued.

Women are an internally differentiated category, intersected by class, race, ethnicity, ability and other differentiations; consequently, gender justice does not coincide with gender equality.

Care Work

Care work is performed in households, communities and the environment, mostly (but not exclusively) by women.

It can be defined as the work of looking after the physical, psychological, emotional and developmental needs of one or more people.

It is a core dimension of social reproduction. Amaia Pérez Orozco describes it as the set of activities that ultimately ensure life, and that acquire meaning within the framework of interpersonal relationships.

Often invisible and unrecognised as work, care takes place in homes, communities and the public sphere, in the urban and rural environment, on the land, and in many earth systems where people meet subsistence needs. Care work is a competence that does not “naturally” flow from the disposition of a particular group of people (women), because it is learned through social processes that include experiences and rational operations. Care is also an ethics, i.e. a political principle to transform the economy and society into intrinsically caring systems.

Care Work

Care work is performed in households, communities and the environment, mostly (but not exclusively) by women.

It can be defined as the work of looking after the physical, psychological, emotional and developmental needs of one or more people.

It is a core dimension of social reproduction. Amaia Pérez Orozco describes it as the set of activities that ultimately ensure life, and that acquire meaning within the framework of interpersonal relationships.

Often invisible and unrecognised as work, care takes place in homes, communities and the public sphere, in the urban and rural environment, on the land, and in many earth systems where people meet subsistence needs. Care work is a competence that does not “naturally” flow from the disposition of a particular group of people (women), because it is learned through social processes that include experiences and rational operations. Care is also an ethics, i.e. a political principle to transform the economy and society into intrinsically caring systems.

Social Reproduction

Feminist political economy defines social reproduction as:

the processes, mechanisms and institutions upon which societies and communities, as well as power and production are built.

Three main aspects of social reproduction can be identified [Bakker & Gill, 2003]:

1) biological, or intergenerational reproduction

2) reproduction of labour power

3) reproduction of social relations, via social practices connected to caring, socialisation and the fulfilment of human needs

Social reproduction is the reproduction of the totality of social life, which includes not only material life and modes of production, but also the way of life, social values and cultural and political practices associated with them.

Value: production vs reproduction

Gender and value constructs are deeply co-constitutive. Gender norms associate value with the production of commodities, and devalue social and environmental reproduction, assigning it to socially marginalised subjects, mostly (but not exclusively) women. Consequently, gender justice cannot be achieved without also transforming value.

GDP accounting severely underestimates human and nonhuman reproduction and care work (or the “production of life”). At the same time, it includes activities, such as war and fossil fuel extraction, which deplete and degrade humans and the environment as value-producing.

We must remain critical of gender equality approaches which reinforce existing valuation mechanisms, and exclude reproductive work from the sphere of what counts. Yet, many feminist scholars reject the strategy of displacing unpaid care work to the monetised economy, as this reinforces the structural separation between a (valued) productive sphere and a (devalued and mostly invisible) reproductive sphere.

Re-Productivity

Some Feminist Ecological Economics scholars propose to measure wealth in terms of social provisioning and re-productivity, rather than growth of productivity. The concept of re-productivity arises from the need to (re)integrate production into its social and ecological context, encompassing all reproductive functions. To Adelheid Biesecker, & Sabine Hofmeister, a re-productive economy would “link production of goods and services for concrete people with the restitution – with conservation and regeneration – of the conditions on which economic activity are based”.

A Social Provisioning approach allows for a broader understanding of the economy, including unpaid and nonmarket activities, framed as interdependent social processes. Marilyn Power summarises the main components of Social Provisioning as:

- Centrally embedding unpaid and caring labour within economic analysis.

- Considering human and environmental wellbeing as a central criterion of economic evaluation.

- Considering power inequalities as structural drivers of economic and environmental performance.

- A preference for qualitative analysis and ethical judgments. Valuing what cannot be commodified or quantified.

- Avoiding overly general statements about women’s relationship with nature.

Subsistence Production

Subsistence production is not oriented towards the accumulation of capital, but towards the satisfaction of direct human needs, or the production of life in its widest sense. Subsistence is defined as a way of looking at the economy based on the collective creation and maintenance of a good life with others. Examples include small-scale farming, farmers markets, and urban gardening. All these practices take place through neighbours and communities with principles of mutual aid and reciprocity. The concept is associated with the path-breaking work of German sociologist Maria Mies, who situated her critique of growth at the intersection between capitalist, colonial and patriarchal structures.

Gender Justice and the Circular Economy

The Circular Economy holds important potential for promoting gender justice, though this has received a lack of attention so far. A Gender Just CE requires a broader transformation of valuation mechanisms, redefining the value produced in a CE as formed by both paid and unpaid work. Gender justice does not mean including women in the value-oriented CE, but a transformation which would centrally embed care. To be gender just, the CE must aim at closing the loop between productive (i.e. valued) and reproductive (i.e. devalued) work.

A recent report on CE and gender from the Industrial Development Organization of the United Nations shows:

- an over-representation of women in “low-value added, informal and end-of- pipe activities” of the circular economy, including recycling, reuse and waste management”

- an under-representation of women in “higher value-added circular activities” such as industrial eco-design, the development of circular products and other activities involving greater use of advanced technologies”

Yet, a gender just solution should look beyond gender equality towards the root causes of gender discrimination, and question the unequal valuation of different sectors of the CE. By adopting the lens of social reproduction and care work, the relationship between human beings and the biosphere appears substantially different than when focusing on production or consumption.

The key question then becomes how to rethink and (re)organise the CE in a way that incorporates, recognises, and values social reproduction and care work.

CE Case Study: Community Composting in New York City: Practices of Collective Care

Oona Morrow & Anna Davies present a study of community-led composting practices in New York City as an example of circular practices which may be interpreted through a feminist lens of care. Community composting is a practice whereby “food waste is processed close to the sources where they are generated, to capture the benefits of both the process, and the finished product for the community”. Consequently, benefits include social cohesion, individual wellbeing, and education, providing more than just an alternative method of transforming waste. This contrasts with market-oriented CE approaches which are based on profit-maximisation, extracting additional value from waste which becomes a commodity, these typically necessitate economies of scale and complex logistics networks.

The NYC Community Compost Project has provided over 30 years of outreach, education, and funds to grassroots sustainability organisations. This has been crucial to facilitating the behaviour change, and education necessary to make composting accessible to communities and organisations across the city.

Of the four sites investigated by Morrow and Davies, all imply a significant involvement of municipal agencies: located on public property, these initiatives rely on not only unwaged but also waged labour, paid for by the municipality. Nevertheless, they are all run by non-profit organisations, and work with donated waste, which they give back to the community as gifted compost, co-produced and shared with the communities they are embedded in. This bypasses the spatial injustice of centralised municipal composting facilities, which move large quantities of waste into poorer communities of colour, thereby country environmental injustice.

Community composting thus offers a ‘diverse economies’ perspective, in which value is reassessed to encompass positive social impacts beyond monetary logic.

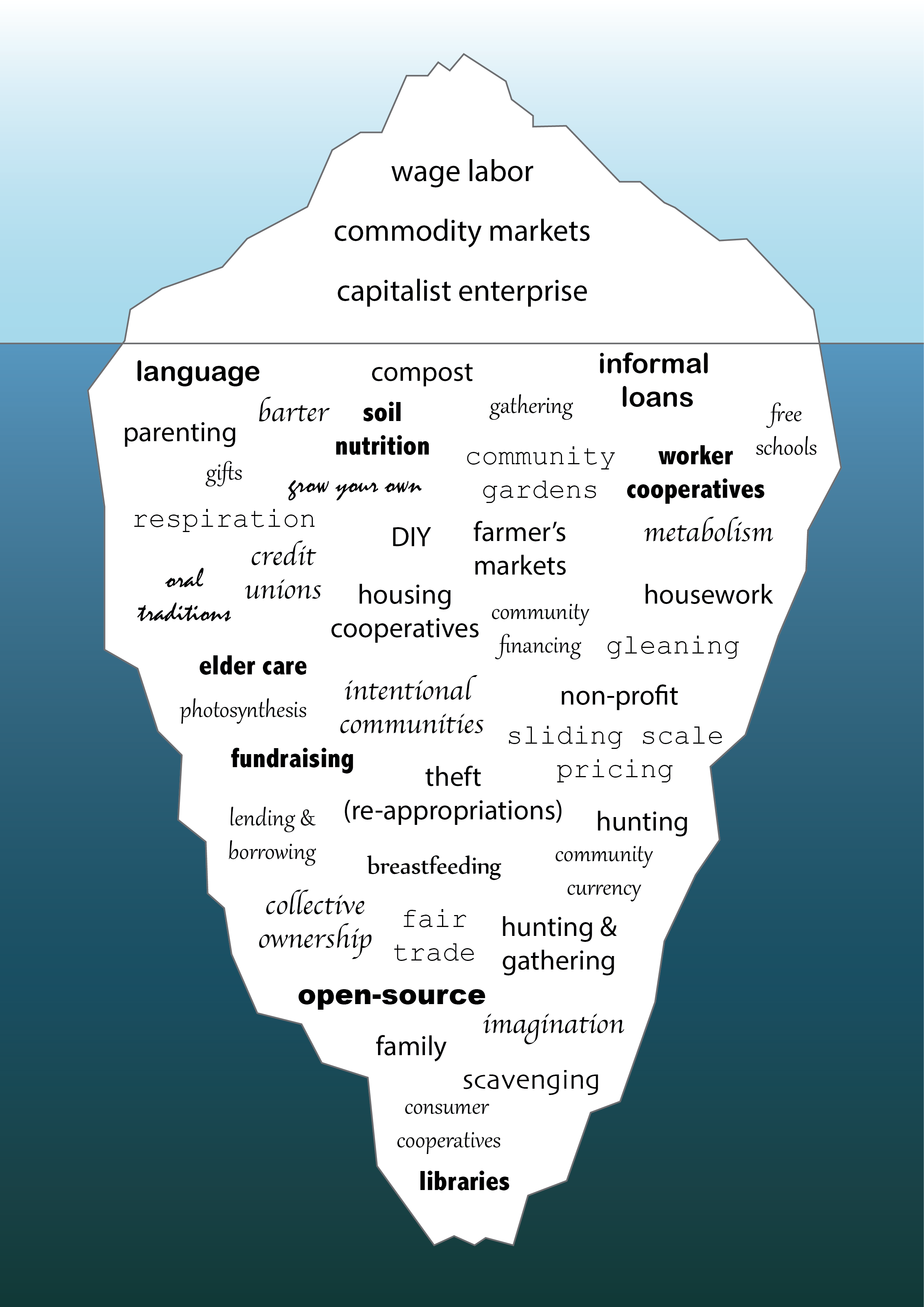

Diverse Economies Iceberg by Community Economies Collective is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Diverse Economies

Since the 1970s, feminist political economy has investigated the nexus between production, reproduction, and gender, allowing to expand and deepen our understanding of gender as related to work and to “the economy” more broadly. It is thus claimed that the formal economy, or production for the market, is only one aspect of the overall economic picture, which would collapse without the human, social and ecological reproduction, which largely takes place outside the market.

The diverse economies iceberg captures activities beyond the formal economy. Whilst the tip of the iceberg represents transactions which are included in the formal economy (via money), constituting the sphere of ‘production’, the base represents activities which are typically excluded, and yet are necessary to the very existence of the former. These are conceptualized under the category of ‘reproduction’.

Dominant sustainability and CE discourse neglects these diverse means of social reproduction, as well as the “interconnectedness” between the spheres of production and reproduction.

Case Studies

Fast Fashion: the garment industry

The second biggest polluting industry globally has a highly gendered workforce (around 75% women and girls), producing roughly 80 billion items a year. Garment workers are often migrant women that have moved to industrial zones, leaving behind children to be cared for, meaning that unpaid and gendered labour sustains this activity in ways that frequently undermine women’s rights. It is thus crucial for CE considerations within the garment industry to embody a gender justice perspective. [Read more].

Clothing factory in Bogor, Indonesia. Photo by Rio Lecatompessy on Unsplash.

Thrift Shop in Drummondsville, Canada. Photo by Julien-Pier Belanger on Unsplash

Reuse and Thrift Shops

Reuse via thrifting and charity shops can be characterised as an invisible care work because it is often unpaid work done by mostly women volunteers, which does not generate market value. A study by Brieanne Berry highlights the labour of managing the daily overwhelming flow of used stuff, which the author defines as ‘donation dumping’, i.e. a practice that frees consumers of guilt, implicitly encouraging more consumption, and depleting the labour of volunteers. Berry proposes framing CE as an effort at closing the loop between production and reproduction by expanding our understanding of CE towards including care work.

Social Provisioning